Chromobotia macracanthus

Clown Loach

SynonymsTop ↑

Cobitis macracanthus Bleeker, 1852; Botia macracanthus (Bleeker, 1852); Botia macracantha (Bleeker, 1852)

Etymology

Chromobotia: from the Greek khroma, meaning ‘colour’, and the generic name Botia in reference to this species bright colour pattern.

Classification

Order: Cypriniformes Family: Botiidae

Distribution

Native to the Greater Sunda Islands of Borneo and Sumatra. In the former it’s restricted to river systems of Kalimantan Barat (West Kalimantan), Kalimantan Tengah (Central Kalimantan) and Kalimantan Timur (East Kalimantan) provinces in the Indonesian portion including the Kapuas and Kayan.

In Sumatra it’s found in eastern and southern drainages of Jambi, Sumatera Selatan (South Sumatra) and Lampung provinces including the Batang Hari, Musi and Tulang Bawang.

The type series was collected from ‘Palembang’ and ‘Kwanten’ on Sumatra, the former most likely referring to the Musi River and the latter to modern day Kuantan Singingi, Riau province meaning the Indragiri River basin was the probable collection locality.

Populations from the two islands are known to exhibit differences in genetic structure, patterning (see ‘Notes’) and adult size (see ‘Maximum Standard Length’), and it’s been suggested that these may turn out to be distinct species if a detailed study was conducted.

Habitat

Mostly inhabits main river channels but migrates upstream into smaller tributaries to spawn during the wet season, when some areas become temporarily flooded.

The fish are therefore found in different habitat-types depending on the time of year, and the habitats themselves also vary; water flow and depth tend to increase significantly during the wet season, for example. Turbidity and pH typically also rise during this time while water temperature drops.

Age also plays a part, with juveniles remaining in the floodplainbreeding grounds for several months whereas the adults typically return to the main rivers post-spawning with very old individuals probably not migrating at all (see ‘breeding’).

The majority of its native rivers contain soft, tea-coloured water and pass through areas of rainforest, although much of what once existed has now been degraded.

In the floodplain swamp forests marginal vegetation is normally thick with shade provided by the forest canopy above. Substrate consists largely of detritus and leaf litter with submerged tree roots, trunks, patches of previously emerse vegetation, while the water tends to be almost still.

Fish species diversity in these zones is typically quite high as many move here to feed and spawn, and in an article published in 2009 by the German magazine ‘Amazonas’ Hans-Georg Evers recorded no less than 40 in the floodplain of the Sungai (river) Pijoan, part of the lower Batang Hari drainage.

Among these were several known to the aquatic trade, including Brevibora dorsiocellata, R. einthovenii, Trigonopoma pauciperforatum, Trigonostigma hengeli, Betta falx, Luciocephalus pulcher, L. aura, Nandus nandus, Chaca bankanensis, Mystus spp. and many more.

In the main river channels the story is rather different; these can flow swiftly during the wet season, less so during the dry months, and submerged vegetation is uncommon. Here larger, pelagic species from genera such as Barbonymus, Labeo and Pangasius can be found.

Maximum Standard Length

Supposedly exceeds 400 mm but reports from its native rivers suggest an average adult size between 200 – 305 mm, borne out by the largest aquarium specimens we know of.

It’s possible that very old female individuals might grow bigger but this is likely to take a long time since growth tends to slow down considerably once the fish reach 150 – 200 mm.

Aquarium SizeTop ↑

A tank with base measurements of 180 ∗ 60 cm or equivalent is the absolute minimum required to house a group, and young specimens should only be grown on in smaller aquaria if several partial water changes are conducted each week.

Maintenance

All botiids need a well-structured set-up although the actual choice of décor is more-or-less down to personal taste.

A natural-style arrangement could include a substrate of sand or fine gravel with lots of smooth, water-worn rocks and pebbles plus driftwood roots and branches.

Lighting can be relatively subdued and plants able to grow in such conditions like Microsorum pteropus (Java fern), Taxiphyllum barbieri (‘Java’ moss) or Anubias spp. can be added if you wish. These have an added benefit as they can be attached to pieces of décor in such a way as to provide useful shade.

Otherwise be sure to provide plenty of cover as botiids are inquisitive and seems to enjoy exploring their surroundings. Rocks, wood, flower pots and aquarium ornaments can be used in whichever combination to achieve the desired effect.

Bear in mind that they like to squeeze themselves into small gaps and crevices so items with sharp edges should be omitted, and any gaps or holes small enough for a fish to become trapped should be filled in with aquarium-grade silicone sealant. A tightly-fitting cover is also essential as these loaches do jump at times.

Although botiids don’t require turbulent conditions they do best when the water is well-oxygenated with a degree of flow, are intolerant to accumulation of organic wastes and requires spotless water in order to thrive.

For these reasons they should never be introduced to biologically immature set-ups and adapt most readily to stable, mature aquaria. In terms of maintenance weekly water changes of 30-50% tank volume should be considered routine.

Water Conditions

Temperature: 24 – 30 °C

pH: 5.0 – 7.0

Hardness: 18 – 215 ppm

Diet

Appears to be chiefly carnivorous they will also eat vegetative matter if available, often including soft-leaved aquatic plants. The natural diet comprises aquatic molluscs, insects, worms, and other invertebrates.

In captivity it’s a largely unfussy feeders but must be offered a varied diet comprising quality dried products, live or frozen bloodworm, Tubifex, Artemia, etc., plus fresh fruit and vegetables such as cucumber, melon, blanched spinach, or courgette.

Home-made foods using a mixture of natural ingredients and bound with gelatin are also highly recommended.

Chopped earthworm can also provide a useful source of protein but should be used sparingly, and while it will also prey on aquatic snails it should never be considered the answer to an infestation since it is not an obligate molluscivore.

Once settled into an aquarium it’s a bold feeder and will often rise into midwater at meal times.

Behaviour and CompatibilityTop ↑

Not especially aggressive but don’t keep it with much smaller fishes as they may be intimidated by its size and sometimes very active behaviour.

Slow-moving, long-finned species such as ornamental bettas, guppies and many cichlids should also be avoided as trailing fins can be nipped.

More suitable tankmates include peaceful, open water-dwelling cyprinids, while in larger tanks members of Barilius, Luciosoma, Balantiocheilos and Barbonymus become options.

In terms of other bottom-dwellers it will do well alongside most other bottids. Some cobitid and nemacheilid loaches are also possibilities as are members of Epalzeorhynchos, Crossocheilus and Garra and many catfishes.

As always, thorough research prior to selecting a community of fishes is the best way to avoid problems.

C. macracanthus is gregarious, forms complex social hierarchies and should be maintained in groups of at least 5 or 6 specimens, preferably 10 or more.

When kept singly it can become withdrawn or aggressive towards similarly-shaped fishes, and if only a pair or trio are purchased the dominant individual may stress the other(s) to the extent that they stop feeding.

That said it seemingly requires regular contact with conspecifics, a fact exemplied by a number of behavioural rituals which have been recorded consistently in aquaria (see ‘Notes’).

Sexual Dimorphism

Adult females are normally fuller-bodies and larger than comparably-aged males. Some theories suggest that males also possess a more deeply forked caudal fin but this is unproven as far as we know.

Reproduction

In nature this species is a migratory spawner, moving from the main river channels into smaller tributaries with surrounding, temporarily inundated flood plains during the rainy season.

These movements usually begin in September with spawning typically occurring in late September/early October, though the timing of this is beginning to shift with the changing climate (Evers, 2009).

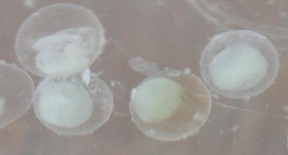

The eggs drift and come to settle in the riparian vegetation and there the initially pelagic larvae spend their early days feeding on micro-organisms. Some drift too far, enter the main rivers and are eventually swept out to sea, and modern-day native fishermen have come to take advantage of this phenomenon (see ‘notes’).

The remaining fry stay in the flooded areas until the waters begin to recede at which point they typically measure around 30 mm SL.

They then move into the smaller tributaries until large enough to complete their passage into the major channels where they remain until sexually mature and able to undertake spawning migrations of their own.

There exist reports suggesting that the Bornean populations inhabiting permanent waters such as the Danau Sentarum lake system do not perform such migrations although we’ve been unable to confirm this definitively as yet.

At one time all traded fish were wild-collected, mostly from Sumatra, but these days the situation is less clear. While many thousands of wild specimens are still caught and sold annually, farmers in Southeast Asia have been artificially breeding the species via the use of hormones for several years.

More recently breeders from the Czech Republic and other parts of Eastern Europe have perfected a similar technique which has seen the price of the once-expensive captive-bred fish drop considerably.

Unfortunately this practice has been taken to a different level in recent years with an apparent hybrid between a Botia species (probably a form of B. histrionica) and C. macracanthus appearing on the market as well as others with questionable body shapes or markings.

Aquarium breeding by private hobbyists remains unheard of and undocumented which given the complexity of the species‘ natural reproductive cycle is perhaps unsurprising.

It’s often been said that the reason for the lack of success is that immature animals were being used and that the species requires many years to become sexually mature, but this would appear not to be the case.

In nature the specimens undertaking annual spawning migrations average 120 – 200 mm SL, and the species seems to become sexually mature at 120 – 150 mm. Larger individuals appear not to migrate and remain in the primary river channels year-round, suggesting they don’t spawn beyond a certain age.

The only substantial observations in private aquaria we know of were made by SF member Colin Dunlop who noticed his group of four adult fish (three males and a single female) swimming in a ‘diamond’ formation with the female at the head in one of his large stock tanks.

The fish were removed and placed in a separate, smaller tank with plastic grating covering part of the base and some lengths of plastic piping. Water temperature was 78.8°F/26°C and pH 4.5, the latter lowered using hydrochloric acid.

After several days Colin noticed “thousands” of eggs on the base of the tank, and on close inspection all four fish were found to be crammed into a single piece of piping out of which hundreds more eggs were falling.

The vast majority fungussed immediately with the others proving infertile shortly after, the general consensus being that moving the fish stressed them and caused the female to expel the eggs without being prompted by the males.

NotesTop ↑

This species is arguably one of the most misunderstood in the hobby since it’s wholly unsuitable for smaller aquaria despite its ubiquitous availability.

Most retailers sell it without providing what should be considered essential information regarding long-term care and most specimens undoubtedly fail to reach their potential in captivity. The purchase of a group is also a considerable investment given that if properly cared for typical life span is in excess of twenty years.

Populations from Borneo and Sumatra are documented to exhibit slight differences in patterning, the most obvious being the presence of black colouration in the pelvic fins of Bornean fish, almost completely black in some specimens.

In contrast the fins of Sumatran examples are a uniform reddish colour. The black band on the caudal peduncle also tends to terminate closer to the fin itself in Bornean than Sumatran fish.

A further observation is that in some Bornean individuals the dark bands on the body develop thin, pale borders although we’re unsure if this is specific to fish inhabiting a particular river drainage, an artefact of age or something else.

The two populations are thought to have diverged from one another around 9.5 million years ago and ‘reintroduction‘ of specimens from Sumatra to Kalimantan in order to rebuild stocks may have already resulted in hybridisation within the native populations there.

It’s now illegal to collect large specimens in Indonesia and annual catches of smaller fish have declined greatly, so native fishermen in some areas have been forced to change their tactics in order to keep trading. Traditionally the most common collection technique involves using lengths of bamboo with openings cut into each segment.

These are normally weighted with stones to make them sink and hung from overhanging or marginal vegetation. The loaches take refuge in these at night and the fishermen return during hours of darkness to collect them.

Smaller specimens of 20 – 80 mm have been collected in this way for many years, usually during the month of February, but numbers have fallen away sharply since the turn of the century.

In the Batang Hari river, Sumatra, a different technique now represents the most productive method of collection.

Here C. macracanthus appears to spawn not only in the flooded tributaries but in the plains surrounding the river itself, and local fishermen now collect the pelagic larvae which drift into the main river channel and grow them on to sell to middlemen or larger distributors. Perhaps as many as 10,000,000 specimens are raised and shipped from the area in this way each year.

C. macracanthus was for many years included in the genus Botia, but in 2004 Kottelat moved it into the new genus Chromobotia in order to tidy up a loose end left open by earlier studies, particularly one published by Nalbant (2002).

He had already split four of the putative monophyletic lineages within the family Botiidae into distinct genera but failed to address this species which is clearly different to all other members.

The main distinguishing features useful to aquarists are the unique colour pattern and adult size but it’s also identifiable by a combination of characters given as follows by Kottelat (2004): mental lobe developed in a barbel; fronto-parietal fontanelle large and elliptical; anterior chamber of gas bladder partly covered by bony capsule, posterior chamber large; top of supraethmoid very broad; optic foramen rather small; suborbital spine not strongly arched and bifid; head naked.

The family Botiidae has been widely considered a genetically distinct grouping since Nalbant (2002), having previously been considered a subfamily (Botiinae) of the family Cobitidae. Nalbant also moved some previous members of Botia into the new genus Yasuhikotakia based on a number of morphological characters.

Later Kottelat (2004) made further modifications to the taxonomy, raising Chromobotia for B. macracanthus and confirming that species previously included in the genus Hymenophysa should instead be referred to Syncrossus.

The former alteration was based on colour pattern plus some morphological characters and the latter because Hymenophysa not only represents a spelling mistake (McClelland’s original spelling was Hymenphysa) but is a junior synonym of Botia.

More recently Kottelat (2012) erected the genus Ambastaia to accommodate A.nigrolineata and A. sidthimunki, two former members of both Botia and Yasuhikotakia.

As a result of these works the family Botiidae is thus divided into two tribes within which Botia appears to be the most basal lineage:

Tribe Leptobotiini – Leptobotia, Parabotia, Sinibotia.

Tribe Botiini – Ambastaia, Botia, Chromobotia, Syncrossus, Yasuhikotakia.

Phylogenetic studies by Tang et al. (2005) and Šlechtová et al. (2006) have largely confirmed this system to be correct although the latter disagreed with the placement of Sinibotia, finding it to be more closely related to the tribe Botiini.

Ambastaia nigrolineata and A. sidthimunki were found to be more closely-related to both Sinibotia and Syncrossus than Yasuhikotakia, despite being considered members of the latter at the time. Šlechtová et al. also proposed the use of subfamily names under the following system:

Subfamily Leptobotiinae – Leptobotia, Parabotia.

Subfamily Botiinae – Botia, Chromobotia, Sinibotia, Syncrossus, Yasuhikotakia.

Within these Botia appears to be the basal, i.e., most ancient, lineage and in a more-detailed phylogenetic analysis Šlechtová et al. (2007) confirmed the validity of the family Botiidae with the genera listed above as members rather then being grouped into subfamilies. This more recent, simpler system is the one we currently follow here on SF.

Some behavioural routines exhibited by botiid spp. have been recorded often enough that they’ve been assigned non-scientific terms for ease of reference.

For example during dominance battles (these occur most frequently when the fish have been introduced to a new tank, or new individuals added to an existing group) the protagonists normally lose much of their body patterning and colouration, a phenomenon that’s come to be known as ‘greying out’.

Such displays will sometimes also happen within an established group as individuals seek to improve social ranking but are usually nothing to worry about.

Interestingly some observations suggest that the character of the highest-ranked, or alpha, fish appears to affect that of the whole group though it must be said that scientific studies of botiid loach behaviour are virtually non-existent.

It certainly seems that they display a degree of ‘personality’ with some specimens being naturally bolder or more aggressive than others, for example. The alpha is normally the largest specimen within the group and often female.

‘Shadowing’ is an interesting behaviour in which younger individuals swim flank-to-flank with older, mimicking their every movement. Some keepers report that more than one smaller fish may shadow a larger simultaneously, with even three or four on each side!

The reason for it is unknown; it may relate to a group staying in touch with one another when rivers swell during times of flooding, perhaps reducing drag by swimming ‘in formation’ or having some other communicative function.

It’s been observed in aquaria with both high and low water flow and seems to be habitual to the extent whereby some individuals will shadow other fishes if no conspecifics are present.

Sound also appears to be an important factor in communication since these loaches are able to produce audible clicking sounds, these increasing in volume when the fish are excited. The behavioural aspects of this phenomenon remain largely unstudied but the sounds are thought to be produced by grinding of the pharyngeal (throat) teeth or subocular spines.

A further curiosity is the so-called ‘loachy dance’ which involves an entire group swimming in a constant, restless fashion around the sides of the tank, usually utilising the full length and height.

The reasons for this are unknown and reports as to when it occurs vary but the most common triggers appear to be the addition of food, fresh water or new conspecifics, and it can last anything from a few minutes to a day or more.

Botiids also often settle at peculiar angles, wedged vertically or sideways between items of décor, or even lying flat on the substrate. This is no cause for alarm and appears to be a natural resting behaviour.

C. macracanthus also possesses sharp, motile, sub-ocular spines which are normally concealed within a pouch of skin but erected when an individual is stressed, e.g., if removed from the water. Care is therefore necessary as these can become entangled in aquarium nets and those of larger specimens can break human skin.

Botiids are also susceptible to a condition commonly referred to as ‘skinny disease’ and characterised by a loss of weight. This is especially common in newly-imported specimens and is thought to be caused by a species of the flagellate genus Spironucleus.

It’s treatable although the recommended medication varies depending on country. Hobbyists in the UK tend to use the antibiotic Levamisole and those in the United States Fenbendazole (aka Panacur).

References

- Bleeker, P., 1852 - Natuurkundig Tijdschrift voor Nederlandsch Indië 3: 569-608

Diagnostische beschrijvingen van nieuwe of weinig bekende vischsoorten van Sumatra. Tiental I - IV. - Evers, H-G., 2009 - Amazonas 24: 18-27

Auf nach Jambi! Prachtschmerlen in ihrem natürlichen Lebensraum. - Evers, H-G., 2009 - Amazonas 24: 28-37

Neue Wege - Prachtschmerlenfang einmal anders. - Kottelat, M., 2004 - Zootaxa 401: 1-18

Botia kubotai, a new species of loach (Teleostei: Cobitidae) from the ataran River basin (Myanmar), with comments on botiinae nomenclature and diagnosis of a new genus. - Kottelat, M., 2012 - Raffles Bulletin of Zoology Supplement 26: 1-199

Conspectus cobitidum: an inventory of the loaches of the world (Teleostei: Cypriniformes: Cobitoidei). - Nalbant, T. T., 2002 - Travaux du Museum d'Histoire Naturelle 'Grigore Antipa' 44: 309-333

Sixty million years of evolution. Part one: family Botiidae (Pisces: Ostariophysi: Cobitoidea). - Nalbant, T. T., 2004 - Travaux du Museum d'Histoire Naturelle 'Grigore Antipa' 47: 269-277

Hymenphysa, Hymenophysa, Syncrossus, Chromobotia and other problems in the systematics of Botiidae. A reply to Maurice Kottelat. - Tang, Q., B. Xiong, X. Yang and H. Liu, 2005 - Hydrobiologia 544(1): 249-258

Phylogeny of the East Asian botiine loaches (Cypriniformes, Botiidae) inferred from mitochondrial cytochrome b gene sequences. - Šlechtová, V., J. Bohlen, J. Freyhof and P. Ráb, 2006 - Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 39(2): 529-541

Molecular phylogeny of the Southeast Asian freshwater fish family Botiidae (Teleostei: Cobitoidea) and the origin of polyploidy in their evolution.

December 7th, 2013 at 3:55 pm

180 cm long tank is not enough for clown loach IMO. While they should be kept as a goup (at least 5-6) and they grow big, the footprint of tank should be at least 210 cm, 240 cm is preferable.

February 6th, 2020 at 4:30 pm

A very interesting and documented paper about my favorite fish. I own 3 groups of 20 each in a large tank,3 meters and one group in an outside fish pond about 4 m long ( i live in Thailand so the climate is appropriate ). I often have some females with eggs .its easy to recognize due to the size of the belly. I could not breed or observe them when they breed but I lost by mistake one female few years ago and open her belly full of eggs ..really a lot .her size was only 17 cm and age 4 years .My botias grow quite fast and become 20 cm in less 4 years .I can share some photos of the female and eggs if it can help in sharing knowledge. I could write so long about this fish which I hope to breed one day naturally .I have a 23 cm female which is full of eggs every 3 months .its so distinct and easy to recognize her belly which increases in size both sides. I also have larger specimen which has grown with me for 9 years .if anyone is interested, I would be happy to share .kind regards thierry