Sinogastromyzon wui

SynonymsTop ↑

Sinogastromyzon intermedius Fang, 1931; Sinogastromyzon sanhoensis Fang, 1931

Etymology

Sinogastromyzon: from the Latin sina, meaning ‘from China’ (used as a prefix in this case), Greek gaster, meaning stomach, and Greek myzo, meaning ‘to suckle’.

Classification

Order: Cypriniformes Family: Balitoridae

Distribution

Known only from parts of the Xi Jiang (West River) watershed, the major affluent of the extensive Zhu Jiang (Pearl River), in Guangxi Autonomous Region and Guangdong Province, southern China.

Type locality is given as ‘San-fang, Lo-ching-shien, Kwangsi, China, elevation 1800 feet’.

Some records are from the the Nan Pan river, a tributary system in the upper part of the drainage although the type locality appears to be within the Liu Jiang basin further east.

The Nan Pan originates in Yunnan province and before entering the Xi is joined by the Beipan Jiang, which flows mostly through Guizhou province, so the possibility that S. wui has a larger range than currently recognised cannot be ruled out.

Habitat

As adults Sinogastromyzon spp. mostly inhabit the middle and upper reaches of rivers and streams and tends to be restricted to stretches of riffles or rapids with swift currents.

S. wui is most abundant in shallow (20 – 60 cm deep) habitats characterised by substrates of pebbles, variably-sized rocks and a lack of aquatic vegetation, for example.

The most favourable habitats contain clear, oxygen-saturated water which, allied with the sun, facilitates the development of a rich biofilm carpeting submerged surfaces.

During periods of high rainfall some streams may be temporarily turbid due to suspended material dislodged by increased (sometimes torrential) flow rate and water depth.

We’ve been unable to obtain any information regarding symapatric species but other fishes occupying broadly similar habitats within the Xi Jiang system include Beaufortia kweichowensis, Erromyzon sinensis, Liniparhomaloptera disparis, Traccatichthys pulcher, Pseudogastromyzon fangi, P. myersi, Vanmanenia pingchowensis, Rhinogobius duospilus, Acrossocheilus, Anabarilius, and Microphysogobio species, among others.

Maximum Standard Length

85 – 110 mm.

Aquarium SizeTop ↑

Minimum base dimensions of 75 ∗ 30 cm or equivalent are recommended.

Maintenance

Since this species is an exclusive resident of riffles and rapids in nature it’s essential to keep it in a tank set up to resemble such a habitat.

Use a substrate of gravel, sand (or a mixture) and add a layer of variably-sized water-worn rocks and boulders. Other décor could include driftwood roots or branches.

While the majority of aquatic plants will fail to thrive in such surroundings hardy genera such as Microsorum, Bolbitis, or Anubias can be grown attached to the décor.

Like many species that naturally inhabit running waters it’s intolerant to the accumulation of organic wastes and requires spotless water at all times in order to thrive.

It’s also essential to provide high levels of dissolved oxygen and water movement so a powerful external filter or two should be installed or additional powerheads and airstones utilised as necessary.

As stable water conditions are obligatory for its well-being this fish should never be added to biologically-immature aquaria, and be sure to use a tightly-fitting cover as it can easily climb glass.

Water Conditions

Temperature: Though mountainous Guangxi has a subtropical climate with average air temperatures varying between 62.6 – 73.4°F/17 – 23°C.

Provided its oxygen requirements are maintained this species can tolerate higher temperatures put for general aquarium care a value within the range 20 – 24 °C is recommended.

pH: 6.5 – 8.0

Hardness: 90 – 268 ppm

Diet

Sinogastromyzon spp. are specialised micropredators and biofilm grazers feeding on small crustaceans, insect larvae, and other invertebrates with some algae taken as well.

In captivity some sinking dried foods may be accepted but daily meals of live or frozen Daphnia, Artemia, bloodworm, etc., are essential for the maintenance of good health and it’s highly preferable if the tank contains rock and other solid surfaces with growths of algae and other aufwuchs.

If unable to grow sufficient algae in the main tank or you have a community containing numerous herbivorous fishes which consume what’s available quickly it may be necessary to maintain a separate tank in which to grow algae on rocks and switch them with those in the main tank on a cyclical basis.

Such a ‘nursery‘ doesn’t have to be very large, requires only strong lighting and in warmer climates can be kept outdoors.

Balitorids are often seen on sale in an emaciated state which can be difficult to correct.

A good dealer will have done something about this prior to sale but if you decide to take a chance with severely weakened specimens they’ll initially require a constant source of suitable foods in the absence of competitors if they’re to recover.

Behaviour and CompatibilityTop ↑

Very peaceful although its environmental requirements limit the selection of suitable tankmates somewhat, plus it should not be housed with any much larger, more aggressive, territorial or otherwise competitive fishes.

Potential options include small, pelagic cyprinids such as Tanichthys, Danio, and Rasbora, stream-dwelling gobies from the genera Rhinogobius, Sicyopterus, and Stiphodon, plus rheophilic catfishes like Glyptothorax, Akysis and Hara spp.

Some loaches from the families Nemacheilidae, Balitoridae and Gastromyzontidae are also suitable but others are not so be sure to research your choices thoroughly before purchase.

Regarding conspecifics it’s best described as ‘loosely gregarious‘ so buy a group of 4 or more if you want to see its most interesting behaviour.

It’s territorial to an extent with some individuals appearing more protective of their space than others (often a prime feeding spot). This may be related to gender since males in some related species are known to be more aggressive than females.

At any rate physical damage is rare and such battles are very entertaining to watch. Sinogastromyzon spp. tend to be quite reclusive compared to most other balitorids and maintaining them in numbers may also help offset this to a certain extent.

Sexual Dimorphism

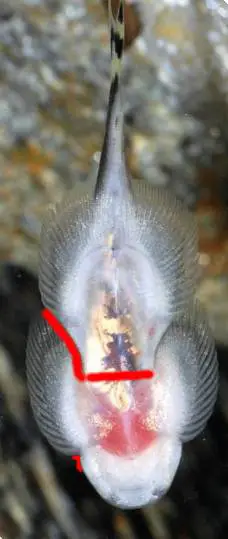

Males have a relatively slimmer body shape, and the angle at which the pectoral-fin meets the head is comparatively sharp, whereas the opposite is true in femaes (see images).

These differences are most obvious when the fish is viewed from above or below.

Reproduction

Nothing has been recorded in aquaria as far as we know but the congener S. puliensis is known to be a seasonal spawner in nature.

It lays demersal eggs and Liao et al. (2008) hypothesised that the fry drift downstream post-hatching before migrating upstream as juveniles following full development of the pelvic region which provides the majority of ‘sucking’ capacity.

The authors also suggested that spawning occurs during the annual rainy season between May and September with upstream migration occurring from August to November.

NotesTop ↑

This species is probably the most common member of the genus in the aquarium trade but still not often exported in numbers.

Instead it’s more often found in mixed shipments of other wild-collected fishes from southern China, particularly Beaufortia or Pseudogastromyzon spp.

It may appear superficially similar to some congeners but can be told apart by the following combination of characters: presence of scales on upper surface of paired fins and the body between underside of pectoral-fin origin and pelvic-fin origin; regular dark blotches present on dorsal surface of body; no band of muscle muscular on the upper surface of the pelvic-fin base.

Kottelat and Chu (1988) referred to the latter feature as ‘axillary lobes’ and gave additional defining characters for the genus (used in combination with those above) as 11-14 simple pectoral-fin rays, 5-8 simple pelvic-fin rays, 47-72 lateral line scales and anal fin with a strong spine.

Sinogastromyzon is distinguished from other balitorid genera by a combination of characters as follows: head and anterior portion of body relatively short, depressed and ventrally flattened; paired fins horizontal and laterally expanded, with 2 or more simple rays; pelvic fins fused posteriorly to form a sucking disk; eyes superolateral; mouth inferior and transverse; 4 rostral and 4 maxillary barbels aligned in rows; gill opening relatively large and extending to pectoral-fin.

The genus currently appears restricted to southern mainland China, Taiwan, Laos, and northern Vietnam.

Sinogastromyzon spp. have specialised morphology adapted to life in fast-flowing water. The paired fins are orientated horizontally, head and body flattened, and pelvic fins fused together.

These features form a powerful sucking cup which allows the fish to cling tightly to solid surfaces. The ability to swim in open water is greatly reduced and they instead ‘crawl’ their way over and under rocks.

The family Balitoridae as recognised by Kottelat (2012) is widely-distributed across much of the Indian subcontinent, Southeast Asia and China.

Kottelat (2012) also considers the family Gastromyzontidae valid and many former balitorids are now contained within that group, but Sinogastromyzon is retained in Balitoridae.

References

- Kottelat, M., 2012 - Raffles Bulletin of Zoology Supplement 26: 1-199

Conspectus cobitidum: an inventory of the loaches of the world (Teleostei: Cypriniformes: Cobitoidei). - Kottelat, M. and X.L. Chu, 1988 - Revue Suisse de Zoologie 95(1): 181-201

A synopsis of Chinese balitorine loaches (Osteichthyes: Homalopteridae) with comments on their phylogeny and description of a new genus. - Lee, T-W., 2000 - Endemic Species Research 1: 13-20

Distribution and Relative Abundance of Sinogastromyzon puliensis in Taiwan. - Liao T-Y., C-C. Pan and C-S. Tzeng, 2008 - Ichthyological Exploration of Freshwaters 19(3): 193-200

Migration of Sinogastromyzon puliensis (Teleostei: Balitoridae) in the Choshui River, Taiwan. - Liao, T-Y., T-Y. Wang, H-D. Lin, S-C. Shen, and C-S. Tzeng, 2008 - Zoological Studies 47(4): 383-392

Phylogeography of the Endangered Species, Sinogastromyzon puliensis (Cypriniformes: Balitoridae), in Southwestern Taiwan Based on mtDNA. - Liu, S-W., X-Y. Chen, and J-X. Yang, 2010 - Environmental Biology of Fishes 87(1): 25-37

Two new species and a new record of the genus Sinogastromyzon (Teleostei: Balitoridae) from Yunnan, China. - Nichols, J. T., 1943 - Natural history of Central Asia. Volume IX. The American Museum of Natural History, New York, USA: 1-322

The freshwater fishes of China. - Wei, Ri-F., L-P. Zheng, X-Y. Chen, and J-X. Yang, 2009 - Zoological Research 30(2): 185-194

Investigation of Fish Resources in Hechi Prefecture of Guangxi Province,with Comparison of Fish Biodiversity Between Two Tributaries. - Wu, F-C. and T-W. Lee, 2002 - River Research and Applications 18(2): 155-169

Effect of flow-related substrate alteration on physical habitat: a case study of the endemic river loach Sinogastromyzon puliensis (Cypriniformes, Homalopteridae) downstream of Chi-Chi Diversion Weir, Chou-Shui Creek, Taiwan. - Yu, S-L. and T-W Lee, 2002 - Zoological Studies 41(2): 183-187

Habitat Preference of the Stream Fish, Sinogastromyzon puliensis (Homalopteridae).